Aspectos educativos de los impactos: La capa de suevita cerca de Fuentes Calientes, cuenca de impacto de Rubielos de la Cérida (España) Continuar leyendo «El afloramiento de la capa de suevita cerca de Fuentes Calientes, Cuenca de impacto de Rubielos de la Cérida (España)»

Categoría: Aspectos destacables

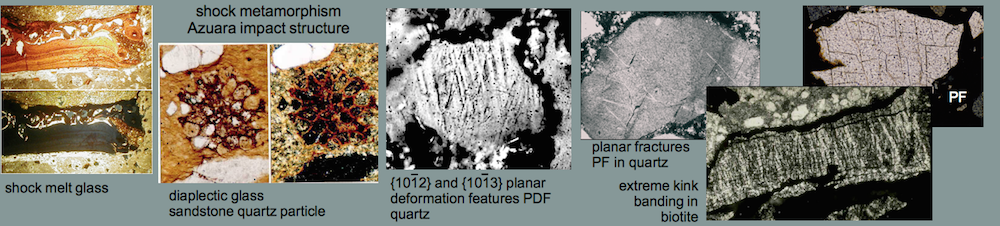

Geología de impacto de Azuara

Eyecta de impacto diamíctico presente en un nuevo afloramiento cercano a Aguilón

por Daniel Gorgas, Ferran Claudin & Kord Ernstson (Octubre de 2013)

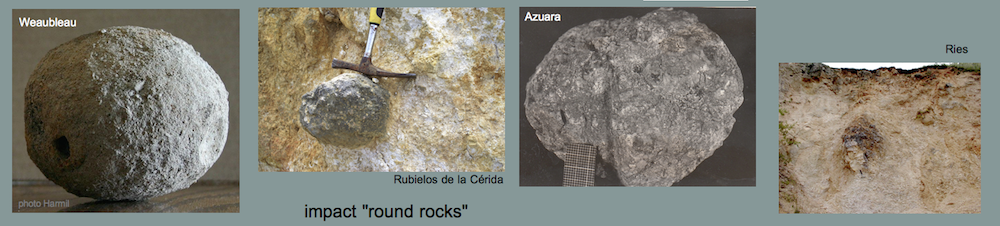

Con ocasión de la ejecución de las obras para la instalación de un aerogenerador cerca del pueblo de Aguilón (Fig. 1), uno de los autores (D.G.) pudo visitar y observar un impresionante afloramiento en geología de impacto (Figs. 2, 3) que se explica prácticamente por si mismo. Un gran bloque redondeado de caliza (probablemente) oncolítica del Malm (Fig. 4) se halla inmerso en la diamictita y en sentido amplio es parte de este deposito diamíctico y polimíctico ubicado en la parte interna Norte del anillo anticlinal de la estructura de impacto de Azuara. Dado que otras posibilidades de formación para explicar este extraordinario afloramiento no son plausibles (p.e. un gran deslizamiento puede ser excluido dada la ausencia de relieve para ello…), el depósito constituye una clara evidencia de eyecta de impacto excavado a partir de la cavidad de impacto de Azuara en expansión. El redondeamiento de esta gran “bola” puede explicarse por rotación y transporte bajo un gran presión de confinamiento ejercida por el material diamíctico en el cual se halla inmersa. Continuar leyendo «Geología de impacto de Azuara»

Nuevas imágenes – La estructura de impacto de Azuara: megabrechificación peculiar cerca de Moyuela

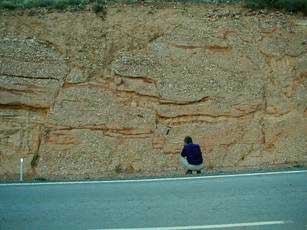

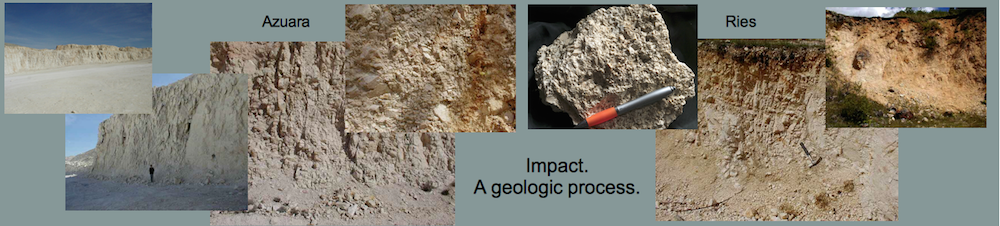

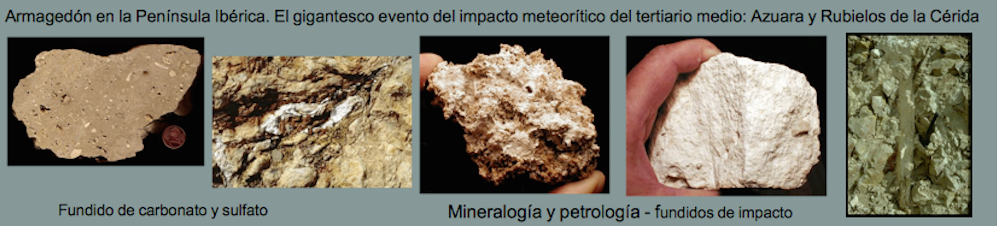

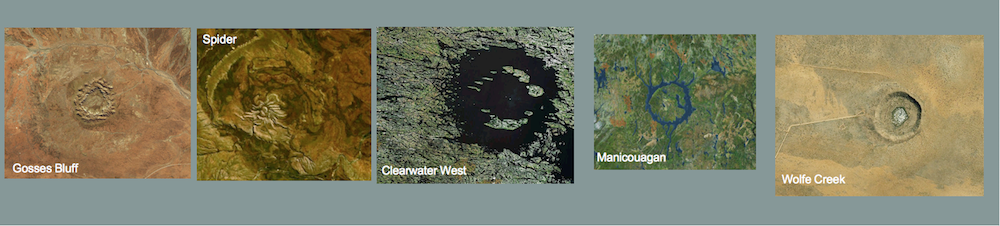

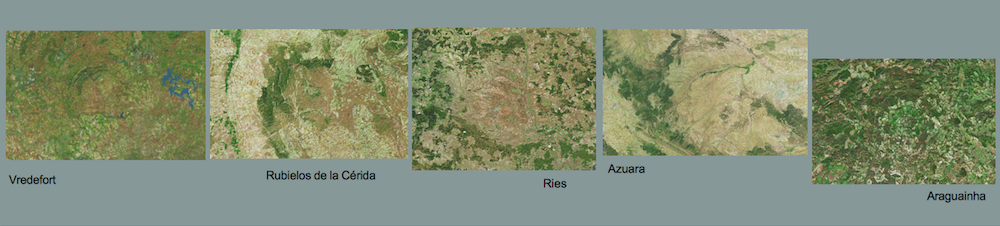

La investigación de las grandes estructuras de impacto de Azuara y Rubielos empezó ahora hace unos 30 años. Desde los inicios de los 80 del siglo pasado hemos mostrado una gran cantidad de excitantes evidencias de este escenario geológico único de la Península Ibérica, a pesar de la agria oposición desde varios lugares, personas y por diversos motivos, que también mostramos a lo largo de la web. Mucho de nuestro material petrográfico y geológico está expuesto aquí en la web, pero es tan sólo una parte de un conjunto más grande. No obstante, hemos decidido ir añadiendo poco a poco material sobre la geología de impacto de Azuara y Rubielos y no renunciamos a pensar que algunos geologos y personas interesadas en la geología lleguen a interesarse en visitar este interesante conjunto de impacto meteorítico de alrededor de 120 Km de extensión.

Empezaremos con un afloramiento fácilmente accesible por carretera sito en el pueblo de Moyuela que queda en medio de la estructura de Azuara (Fig. 1). Este afloramiento nos muestra la enorme destrucción que el impacto ejerció sobre las calizas bien estratificadas del Jurásico, lo cual es inexplicable por la acción “normal” de la tectónica Alpina. Continuar leyendo «Nuevas imágenes – La estructura de impacto de Azuara: megabrechificación peculiar cerca de Moyuela»

Endurecimiento superficial inducido por impacto en clastos pulidos de cuarcita, conglomerados triasicos del Buntsandstein, Norte de España.

Kord Ernstson & Ferran Claudin (2012)

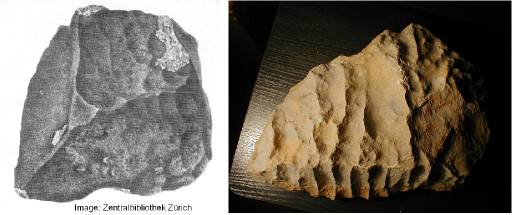

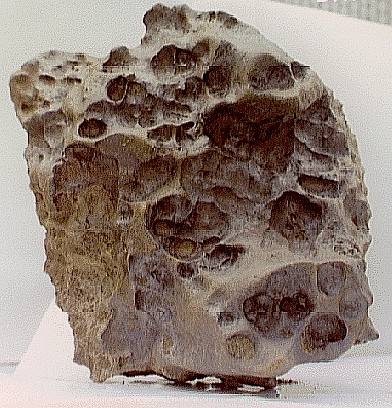

Cantos de cuarcita chocados, ampliamente distribuidos, procedentes de conglomerados triásicos del Buntsandstein han sido citados (Ernstson et al., 2001) como relacionados con el gran evento múltiple de impacto – del terciario medio – de Azuara, que dio lugar a la formación de la estructura de Azuara y la cuenca de impacto elongada de Rubielos de la Cérida (Ernstson et al. 2002, Claudin & Ernstson 2003, Ernstson et al. 2003). Los cantos de cuarcita (y los bloques) están peculiar e intensamente llenos de cráteres y de hoyos (Figs. 1, 2), mostrando en general una fracturación subparalela de espaciado pequeño (Fig. 3). Las características de los cantos se hacen especialmente evidentes cuando son hallados de un modo disperso en el campo como resultado de la meteorización de los conglomerados (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1. Cantos y bloques , procedentes de conglomerados triásicos del Buntsandstein, con las típicas marcas de hoyos, cráteres y pulido (el bloque grande). Continuar leyendo «Endurecimiento superficial inducido por impacto en clastos pulidos de cuarcita, conglomerados triasicos del Buntsandstein, Norte de España.»

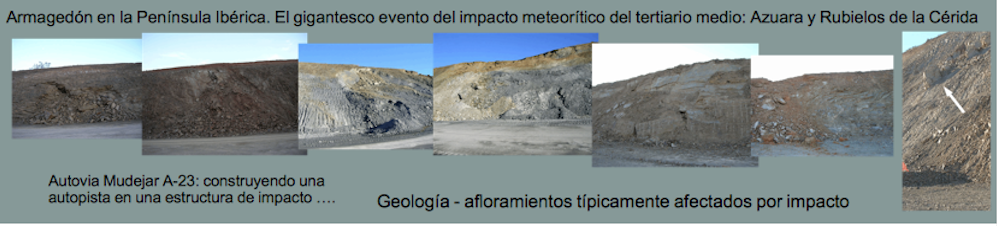

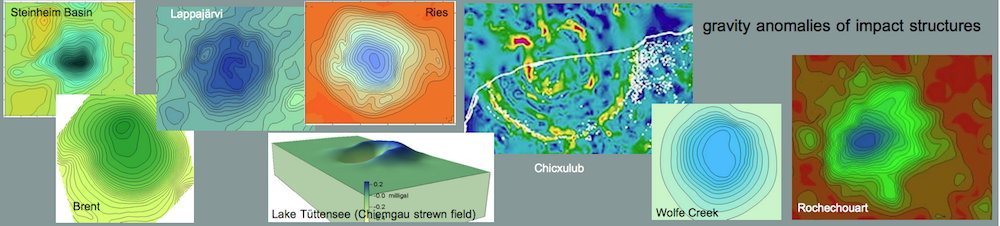

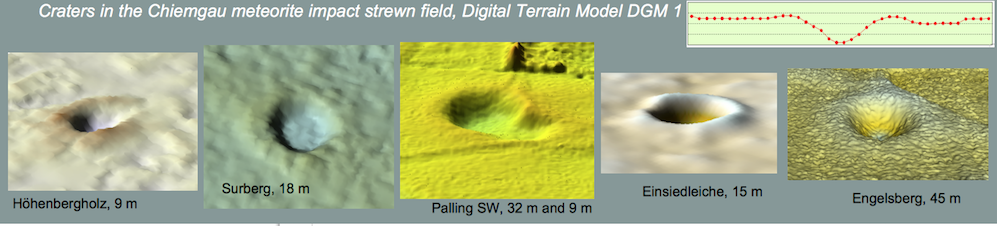

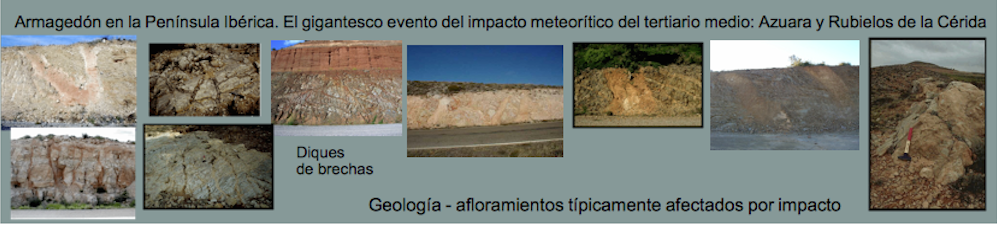

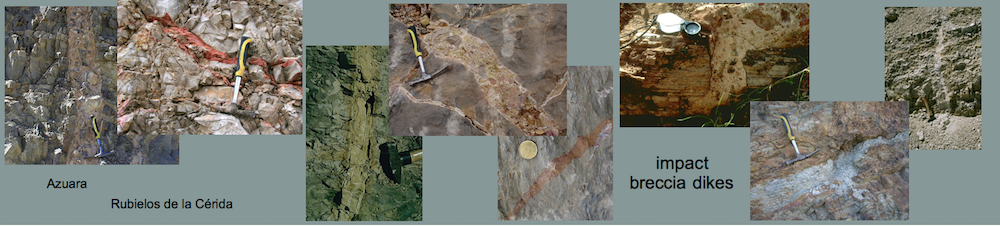

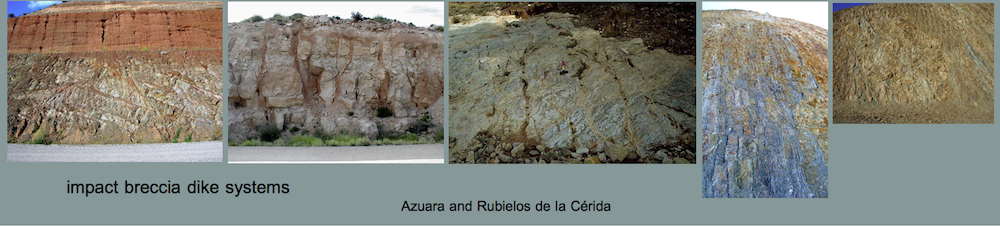

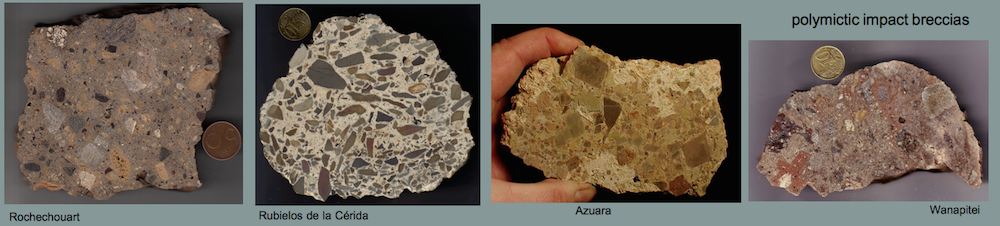

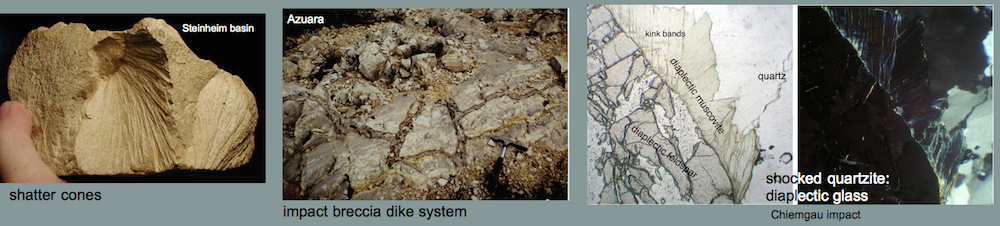

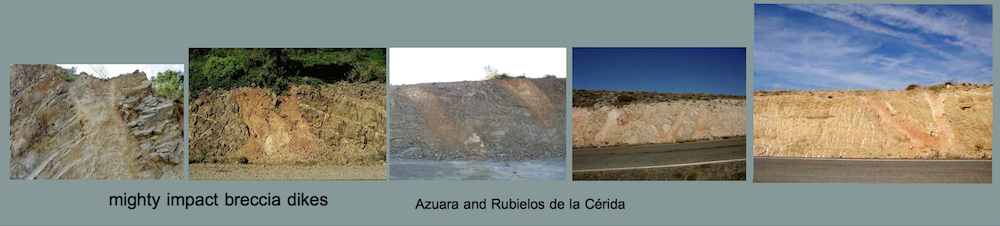

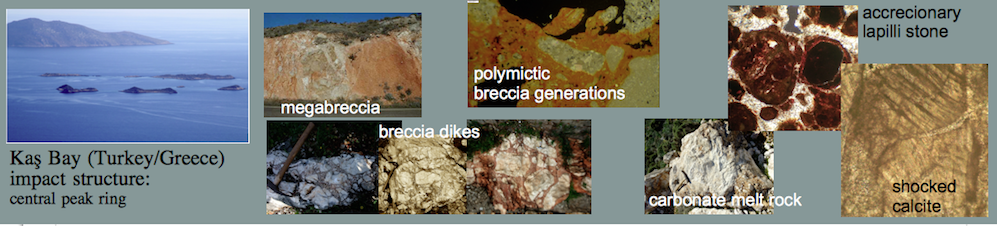

Rubielos de la Cérida impact basin: New impact breccia dikes in Paleozoic silicate rocks

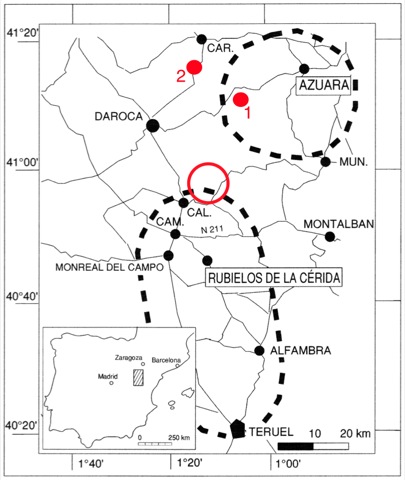

Breccia dikes (dike breccias) are a prominent feature in impact structures, and they have told us a good many about the processes of impact cratering. Among the yet known roughly 200 terrestrial impact structures, Azuara and Rubielos de la Cérida are providing the probably by far best insight into these fascinating geological configurations concerning abundance, exposure accessibility, and diversity with regard to geometry, dimensions and material (also see breccia/dikes; http://www.impact-structures.com/spain; rubielos-breccia-dikes). Recent extensive construction works (storage reservoir, freeway, railroad) near Lechago, Calamocha (CAL; see Fig. 1, red circle) have yielded quite a few nice geological exposures once more documenting the almost everywhere existing impact signature thus underlining that construction work in the large impact region of the Azuara and Rubielos de la Cérida structures may be a hard undertaking – as was impressively shown when the new Autovía freeway line had to cut through the strongly destroyed Paleozoic of the Iberian Chain in the northern rim zone of the Azuara impact structure between Daroca and Cariñena (click here http://www.impact-structures.com/impact-spain/the-azuara-impact-structure/the-2005-autovia-mudejar-geological-exposures/ «The 2005 Autovía Mudéjar geological exposures»).

Below we show images of some newly exposed impact breccia dikes near Lechago exhibiting their characteristic properties and, for comparison, similar dikes and dike systems from the companion Azuara impact structure (location in Fig. 1).

Focusing here on breccia dikes in Paleozoic silicate rocks bears in mind the frequent claim of some Spanish geologists, especially from the Zaragoza university, that the impact breccia dikes are all karst phenomena. Their confusion of breccia dikes with karst features, however, meets some difficulties in the case of silicate siltstones. Also fault breccias can clearly be excluded since these dikes are filled with allochthonous material as is typical for impact-induced highly energetic injection processes.

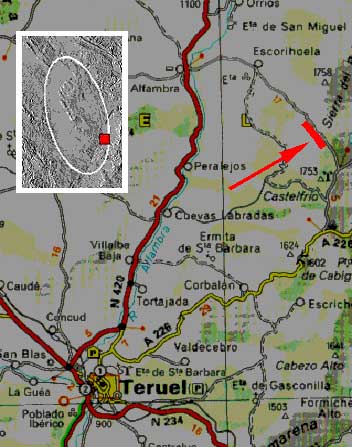

Fig. 1. Location map.

Fig. 1. Location map.

Fig. 2. Thick impact breccia dike cutting through Paleozoic siltstones at the new storage reservoir near Lechago (in the red circle of Fig. 1)

Fig. 2. Thick impact breccia dike cutting through Paleozoic siltstones at the new storage reservoir near Lechago (in the red circle of Fig. 1)

Fig. 3. For comparison: impact breccia dike in Paleozoic siltstones; road to Santuario de la Virgen de Herrera (1 in Fig. 1). Azuara impact structure.

Fig. 3. For comparison: impact breccia dike in Paleozoic siltstones; road to Santuario de la Virgen de Herrera (1 in Fig. 1). Azuara impact structure.

Fig. 4. For comparison: thick impact breccia dikes cutting roughly perpendicular through the bedding of the Paleozoic siltstones. Autovía Mudéjar in course of construction; near Cariñena (2 in Fig. 1). Azuara impact structure.

Fig. 4. For comparison: thick impact breccia dikes cutting roughly perpendicular through the bedding of the Paleozoic siltstones. Autovía Mudéjar in course of construction; near Cariñena (2 in Fig. 1). Azuara impact structure.

Fig. 5. Large system of impact breccia dikes in Paleozoic siltstones at the new storage reservoir near Lechago. Note that the dominant set of dikes is cutting sharply across the bedding (see Fig. 6). In the top: Unfolded post-impact Tertiary sediments.

Fig. 5. Large system of impact breccia dikes in Paleozoic siltstones at the new storage reservoir near Lechago. Note that the dominant set of dikes is cutting sharply across the bedding (see Fig. 6). In the top: Unfolded post-impact Tertiary sediments.

Fig. 6. Segment of the wall in Fig. 5.

Fig. 6. Segment of the wall in Fig. 5.

Fig. 7. For comparison: System of impact breccia dikes cutting sharply through Paleozoic silicate rocks. Autovía Mudéjar in course of construction; near Cariñena (2 in Fig. 2). Azuara impact structure.

Fig. 7. For comparison: System of impact breccia dikes cutting sharply through Paleozoic silicate rocks. Autovía Mudéjar in course of construction; near Cariñena (2 in Fig. 2). Azuara impact structure.

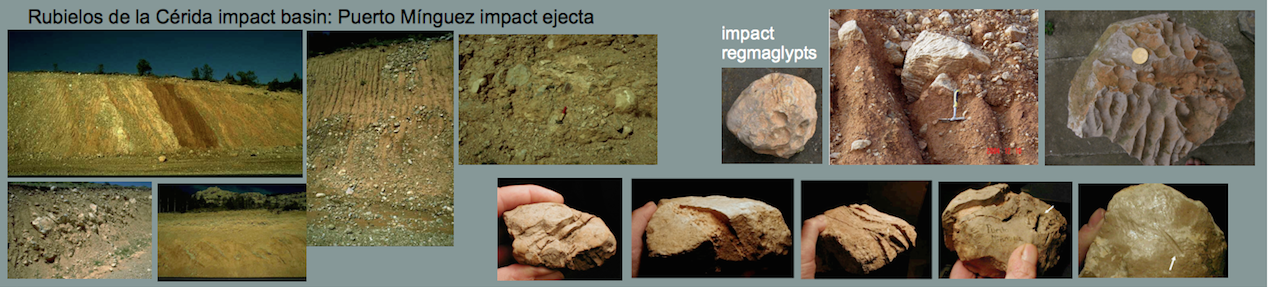

Regmaglypts on clasts from the Puerto Mínguez ejecta, Azuara multiple impact event (Spain)

Fig. 1. Amazingly similar: Regmaglypts on the surface of the Tabor meteorite and on a limestone clast from the Puerto Mínguez impact ejecta.

Among the various deformation features exhibited by the carbonate clasts in the Puerto Mínguez ejecta deposit (striae, nail prints, grooves, rotated fractures, irregular fractures with complex bifurcations, mirror polish, etc), regmaglypted clast surfaces are a prominent feature (Fig. 1). For the first time described by K. Ernstson (2004), they establish clear evidences of an aerial transport of quite a few clasts of the ejecta.

Source: Cascadia Meteorite Laboratory, Portland State University

Fig. 2. A Gibeon meteorite exhibiting distinct regmaglypts.

Regmaglypts (or thumbprints) are reliefs commonly reported for the surface of some meteorites (Figs. 1, 2). The depressions originate from dynamic air pressure [continue …] and from selective erosion by material melting (ablation) off the surface of the meteorite on its passage through the atmosphere. The relief may show polygonal, spherical, rounded or elliptical shape, and a pattern like fingers over wet clay is frequent.

We suggest the ablation features observed in the ejecta have originated from a similar process that is carbonate melting and ablation off the surface on the passage of the ejecta clasts through the heated impact explosion cloud.

Of course, the depressions on the Puerto Mínguez clasts in a way remind of lapiés (karren) features on surfaces of exposed limestones. Lapiés consist of shallow, straight grooves or runnels incised into the limestone by solution. Because of the striae and polish regularly coating the regmaglypted surfaces, and because the regmaglyptic clasts are embedded as individuals in the ejecta matrix (Fig. 3), an in situ formation as lapiés can clearly be excluded.

Fig. 3. The regmaglypted individual embedded in the Puerto Mínguez impact ejecta is incompatible with an in situ dissolution («lapiés» formation).

Alternatively, the «lapiés» depressions existed already before the impact and survived rock fracturing, excavation, and emplacement of the ejecta. This can be excluded because many clasts are regmaglypted all around (Fig. 4), and the frequently observed sharp-edged ridges of the regmaglypts (Fig. 4) would not have survived the excavation and ejection process.

Fig. 4. Front and rear of a regmaglypted limestone clast from the Puerto Mínguez ejecta. The regmaglypts all around and the sharp ridges exclude a «lapiés» formation before excavation and ejection.

In a few cases, the ablation by obvious carbonate melting of the clasts has eaten deeply into the clast (Fig. 5) reminding of similar distinct ablation features of some meteorites (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5. A regmaglypted limestone clast from the Puerto Mínguez ejecta exhibits prominent ablation reaching deeply inside into the limestone clast. For comparison see the meteoritic ablation features in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. The Derrick Peak, Antarctica, meteorite. Image courtesy of NASA.

An extended article on the Puerto Mínguez regmaglypted ejecta including many images can be read here.

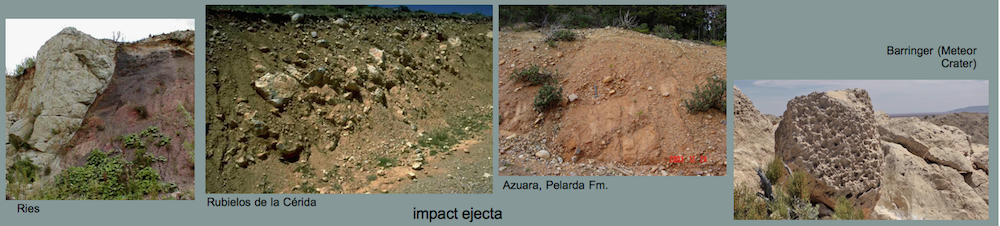

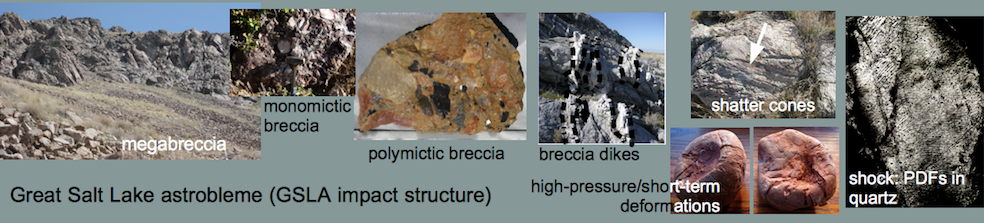

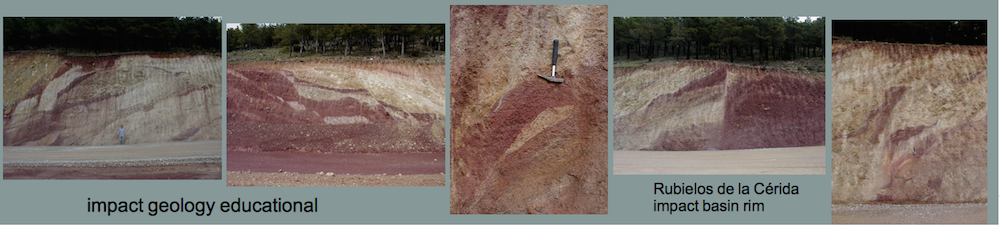

Cutting into an impact crater rim: excavation and modification signature of the impact cratering process

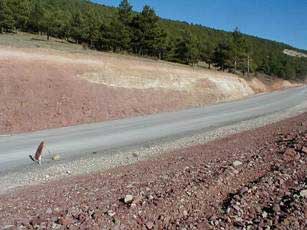

| Road constructors are the friends of the impact geologists. Without their work, most of the highlighting impact outcrops in the Spanish Azuara and Rubielos de la Cérida impact structures would not exist, and many of the rocks typifying impact would not have been discovered. In the last decade, kilometers and kilometers of new geological exposures have been prepared, and we mention the road cuts between Luco de Jiloca and Lechago, at the Puerto Mínguez, between Navarrete and Barrachina, between Fuendetodos and Azuara, between Lécera and Muniesa, between Fuendetodos and Jaulín, and many more. Not only the road cuts but also the many new quarries mostly exploited for road construction material have supplied new geologic outcrops of high geologic importance, as for example the quarries between Belchite and Puebla de Albortón, the many temporary quarries between Navarrete and Barrachina, the large quarries of Corbalán, San Blas, Villafranca del Campo, near Muel, and so on.

The road cut at the crater rim and view down into the Rubielos de la Cérida impact basin.

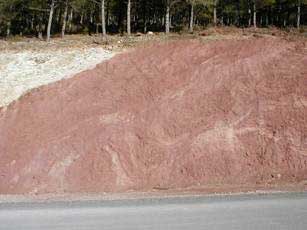

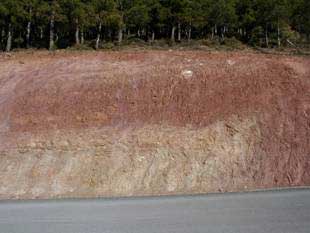

Only recently, the new road cutting into the Rubielos de la Cérida impact basin rim in the ascent between Alfambra/Escorihuela and El Pobo/Cedrillas has prepared a breath-taking extraordinary continuous geologic exposure of currently about 2 km length. The exposure does not show only the unimaginably disastrous forces of the impact excavation and modification of the Permotriassic/Buntsandstein and Muschelkalk rocks leaving a gigantic megabreccia, but also reveals large-scale rock deformations hitherto obviously unknown to geologists. We want to call them stop-and-go deformations.

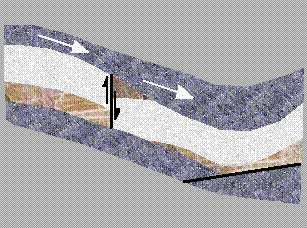

The impact stop-and-go deformation is characterized by a multiple rapid sequence of erosion, sedimentation, folding, faulting and flow in a limited rock unit. This extremely peculiar process is not explicable by “normal“ geological forces and is understood only by the complex impact excavation and modification movements with permanently and in a short time strongly varying stress fields probably supported by the action of water and shock-produced volatiles.

Simple model of stop-and go deformation.

More stop-and-go deformations: megabreccia near Barrachina. Also see http://www.impact-structures.com/impact-spain/the-rubielos-de-la-cerida-impact-basin/megabreccias/ |

|

|

|

|

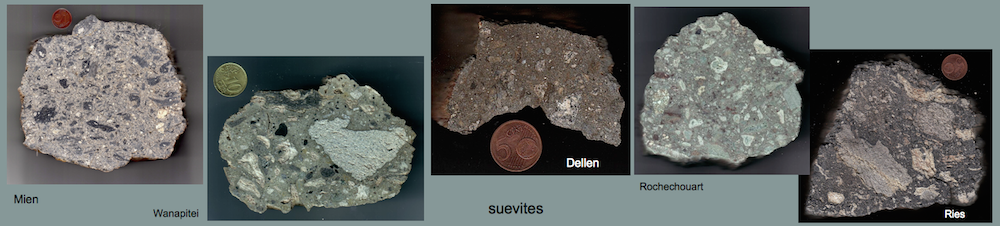

The Jaulín impactite (Azuara, Spain)

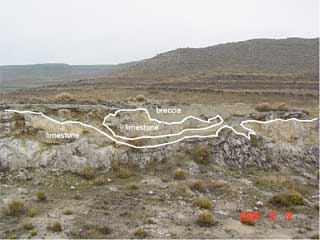

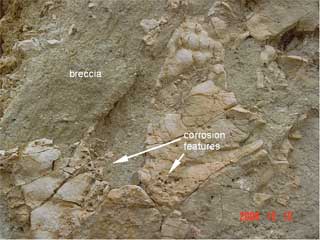

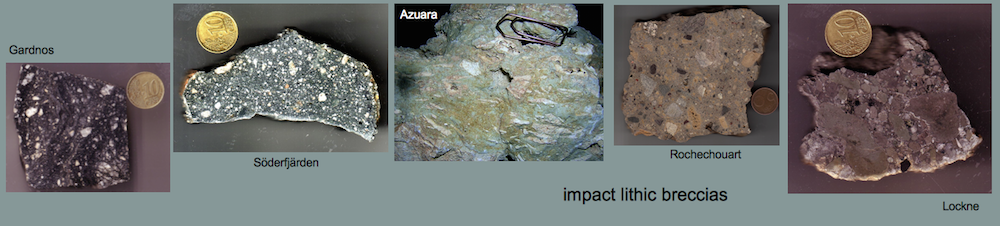

About 30 km north of the center of the Azuara impact structure (Spain) near the village of Jaulín (0°59.3′ W; 41°27.2′ N), a peculiar breccia is exposed. The breccia, not mapped geologically thus far, is intercalated between fossil-rich Jurassic limestones and brownish Miocene(?) gypsum marls. The breccia is unconformably overlying the Mesozoic rocks (Fig. 1) and may penetrate the limestones (breccia dikes, Fig. 2) as well as corrode them (Fig. 3).

On cursory inspection, the greenish rock looks like a massive bone breccia (Fig. 4). On closer examination, the «bones» prove to be limestone clasts having become hollow or more or less completely skeletal (Figs.5, 6).

Beginning (Fig. 7) and complete fragmentation of the clasts is observed. Beside these decomposed clasts, fragments of the limestone host rock are intermixed in the breccia (Fig. 8). They frequently show distinct whitish rims (Fig. 9) which we interpret as the result of beginning decarbonization from enhanced temperatures. Occasionally, the fragmented clasts remain coherent giving evidence of confining pressure upon emplacement (Fig. 10). For the present, it is not clear whether the hollow and skeletal clasts originate also from the local limestones, but from the discussion below we have to assume they are allochthonous.

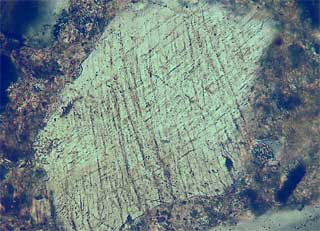

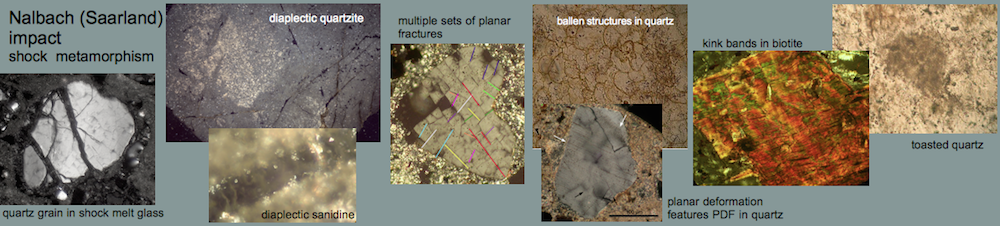

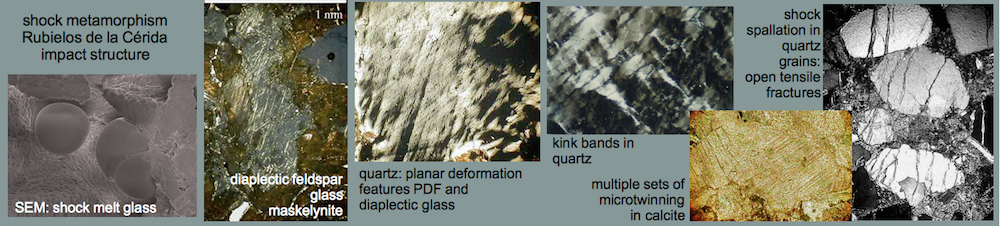

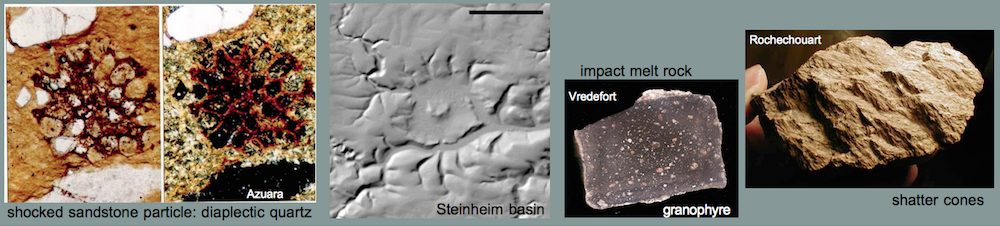

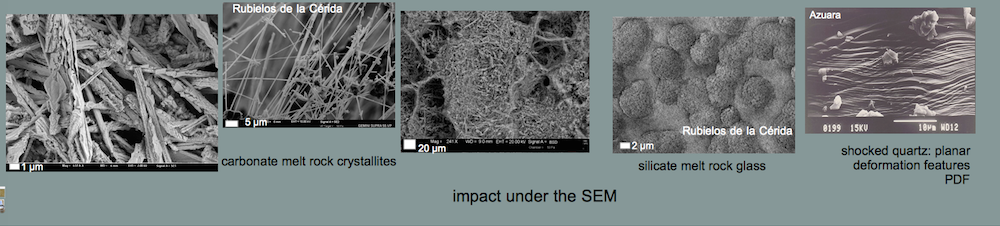

The clasts are immersed in a greenish matrix (Fig. 8) partly exhibiting flow texture as indicated by lined-up small elongated clasts (Fig. 7). In thin section (Fig. 11), the matrix shows to be fine-grained carbonate streaked with irregular bands of poorly rounded quartz grains in a slightly different matrix. Quite a few quartz grains exhibit planar deformation features (PDFs) as in proof of shock metamorphism (Fig. 12).

Breccia formation. – The contacts between breccia and underlying autochthonous rocks as well as the peculiar characteristics of the clasts absolutely exclude a karstification process. A «normal» sedimentation and any diagenetic processes are not consistent with the observations either. From the stratigraphic position at the base of the unfolded Upper Tertiary and from the evidence of enhanced temperatures and of shock metamorphism we conclude the breccia to be an impactite related with the formation of the Azuara structure in the giant multiple impact event that, beside the Azuara structure, formed also the large Rubielos de la Cérida impact basin and crater chain (see http://www.impact-structures.com/spain/). We explain the breccia to be impact ejecta excavated from a region in the Azuara structure where shock intensities were enough to decarbonize and melt limestone cobbles and boulders and to produce PDFs in quartz grains contributing to the breccia matrix.

Hollow and skeletal limestone boulders, cobbles and pebbles are not uncommon in the impact region, and they have been found in e.g. the basal suevite breccia (see suevite) and the impactite from Almonacid de la Cuba (see peculiarities). The process of the decomposition obviously confined to the interior of the clasts is not completely understood thus far, but we suggest two possibilities that must not exclude one another. The clasts belonged to Lower Tertiary conglomerates in the target, and they experienced

- a shock concentration in the cobbles’ interior by shock-wave reverberation and focusing effects

and/or

- a shock heating of the cobbles and a rapid external cooling upon ejection, only allowing the interior to be decarbonized and melted.

On excavation and ejection, the shocked limestone clasts were mixed with the greenish matrix material possibly originating also from the Lower Tertiary. The emplacement was a process of ballistic erosion and sedimentation (Oberbeck 1975) under high pressure (penetration into the Jurassic host rock that was partially fragmented and incorporated into the breccia) and still enhanced temperatures (partial decarbonization of the host rock).

With regard to its stratigraphical position, the Jaulín impactite must be seen as a special variety of the Azuara/Rubielos de la Cérida basal breccia, and, due to the observed shock effects and the relics of probable carbonate melt, as a special type of a suevite breccia (see IUGS classification, the_suevite_page).

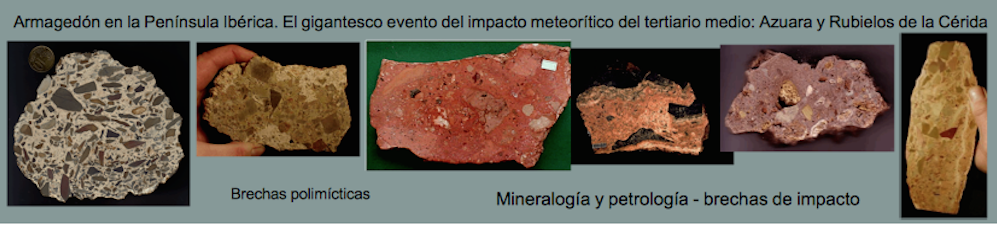

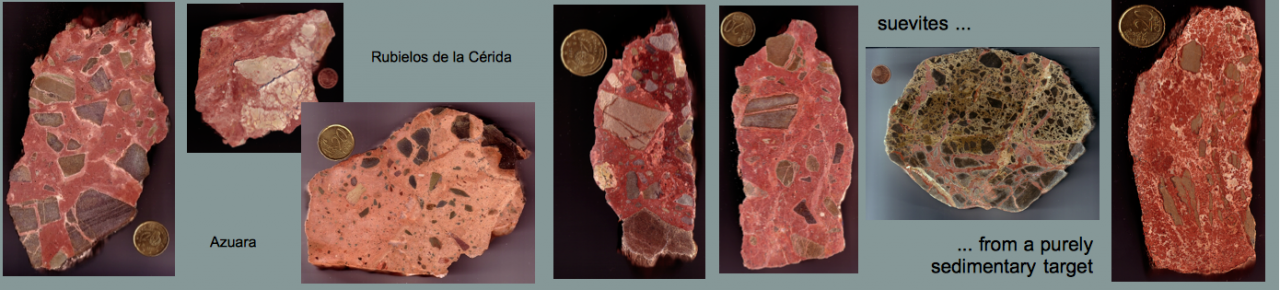

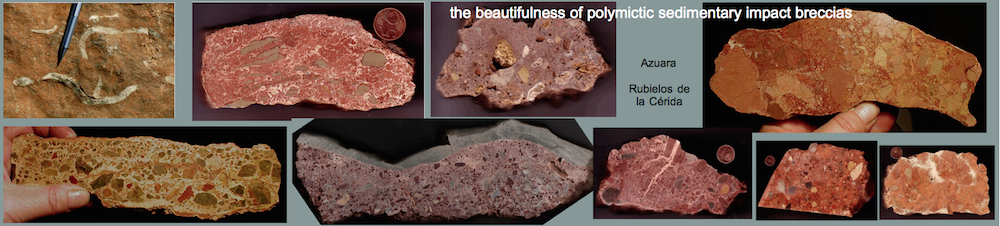

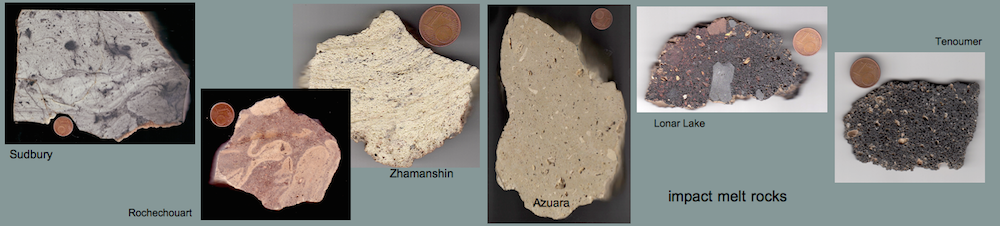

New varieties of the basal suevite breccia from the multiple-impact area in northern Spain

This peculiar polymict breccia uniformly exposed at the base of the unfolded Upper Tertiary over a distance of at least 120 km is a strong clue to the Mid-Tertiary multiple impact in northern Spain. A lot has already been said and written about this breccia (Ernstson & Fiebag, 1992; Ernstson & Claudin 2002, Ernstson et al. 2003; Claudin & Ernstson 2003; http://www.impact-structures.com/impact-rocks-impactites/the-suevite-page/suevites-from-the-azuara-and-rubielos-de-la-cerida-spain-impact-structures/, http://www.impact-structures.com/impact-spain/the-rubielos-de-la-cerida-impact-basin/basal-suevite-breccia-in-the-rubielos-de-la-cerida-impact-basin/), and that is why we confine ourselves to show some new varieties exposed about 2 km northeast of Olalla in the rim zone between the Azuara impact structure and the Rubielos de la Cérida impact basin. We point to the dominating Paleozoic and Triassic components, to the flow texture, to halos around many clasts, to the remarkable fitting of fragmented clasts, to breccias-within-breccias, and we think that some of the breccias are simply beautiful.

Here, we want to mention that regional geologists from the Zaragoza university and the Madrid Center of Astrobiology (Ángel Luis Cortés, Marcos Aurell, Enrique Diaz-Martínez, and others), which basically deny an impact in that region, consider this typical breccia a lacustrine sediment or even a conglomerate (Aurell et al. 1993; Cortés, Nov. 6, 2002, Heraldo de Aragón).

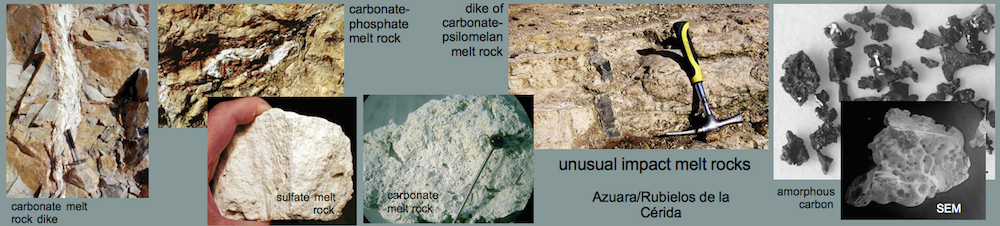

Impact-induced carbonate-psilomelane vein in the Azuara structure of northeastern Spain

Outcrop of Muschelkalk dolomite crosscut by a dark vein of impact melt rock in the vicinity of Monforte de Moyuela.

Black vein under the microscope: light matrix of carbonate minerals (Cc), black particles and gas vesicles (gv). Long side of the figure is about 1 mm.

The full article can be read here:

http://www.uni-wuerzburg.de/mineralogie/schuessler/Monforte-vein.pdf

key words: Azuara impact structure, Rubielos de la Cérida impact structure, carbonate melt, breccia dike, manganese, quench crystallization.

Location map.

Location map.