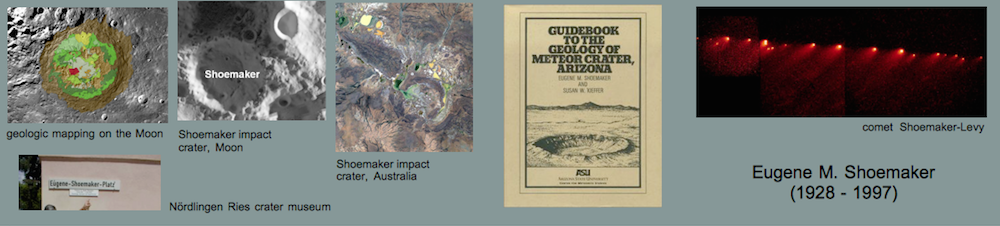

AZUARA IMPACT STRUCTURE (SPAIN) CURVED JOINT SETS: INDICATION OF IMPACT-INDUCED FRACTURING

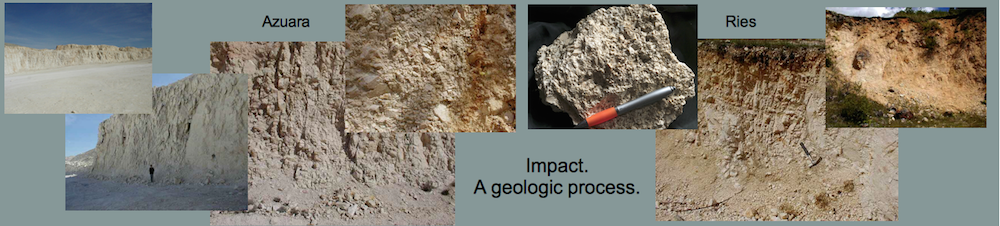

Azuara impact structure (Spain), Ries impact structure (Germany): impact as a geologic process

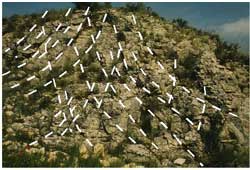

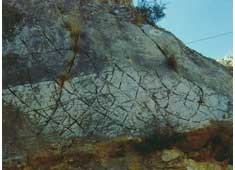

| A few kilometers outside the northern ring of the Azuara impact structure near Belchite, a handful of isolated large blocks of Jurassic limestones emerge from the post-impact Upper Tertiary Ebro basin sediments. Quarrying in these blocks has enabled instructive insight into the drastic impact deformations experienced by very large rock volumes. | |

A A |

B B |

| Image A shows part of a large quarry located at UTM coordinates 0687000, 4583000. The visible length in the image is roughly 300 m. The limestones are drastically destroyed through and through to form a more or less continuous breccia displaying grit (gries) brecciation and mortar texture (see Images B – E). |  C C |

D D |

E E |

| Comparable strong and continuous deformations (Images F, G) can be observed in a limestone quarry located in another block at UTM coordinates 0683000, 4583000. | |

F F |

G G |

| H and I Ries impact structure; Iggenhausen quarry | |

H H |

I I |

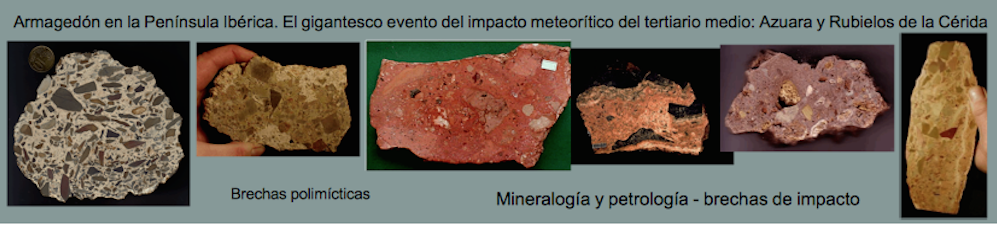

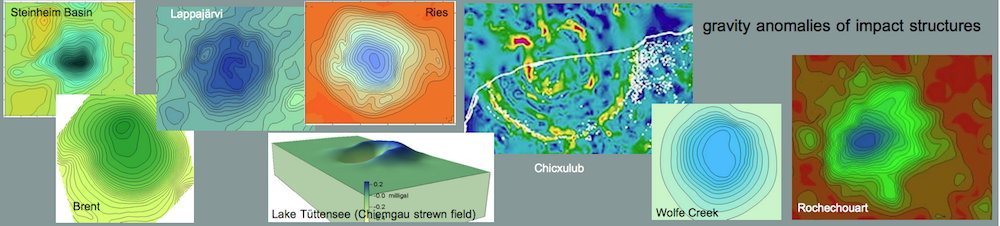

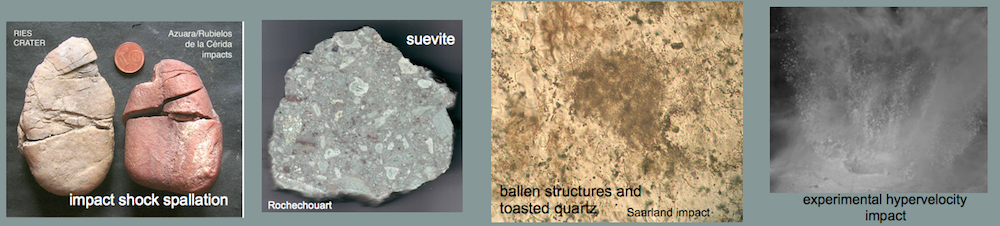

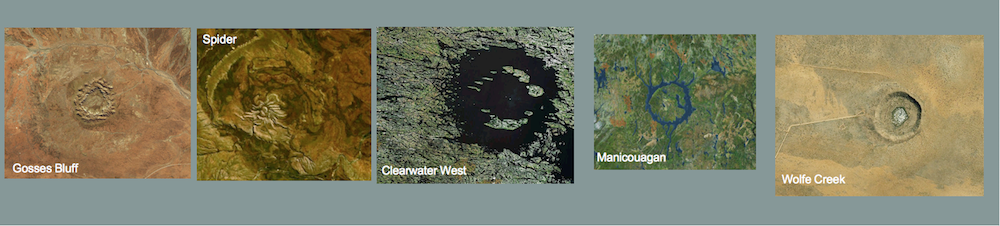

| Comment: The Azuara region and the Jurassic limestones underwent Alpidic tectonics with some folding and block faulting, but we emphasize that Alpidic tectonics can not possibly have caused these disastrous deformations over hundreds of meters. Impact cratering is the only reasonable process to have produced this impressive geologic scenario, and the same deformations are well known to occur in large allochthonous limestone megablocks ejected from the 25km-diameter Ries impact structure (Germany) (Images H, J; Iggenhausen quarry).We suggest that those geologists from the Zaragoza university and the Center of Astrobiology (Madrid) vehemently refusing an Azuara impact visit these highlighting outcrops. Since they like to contrast the Azuara structure with the Ries crater (see their MAPS paper referred to in the Controversy section), they will get a lot of illustrative material.There is one more point we want to refer to. As already said, impact is the only reasonable geologic process that explains these desastrous and voluminous deformations. In other words, there’s actually no need for the well documented strong shock effects in Azuara polymictic breccias to establish Azuara as an impact structure (see below in the Archives and http://www.impact-structures.com/impact-spain/the-azuara-impact-structure/shock-effects-shock-metamorphism-in-rocks-from-the-azuara-impact-structure/ ). The outcrops under discussion here are as well a convincing proof.Usually, the impact nature of a structure under discussion is established by the occurrence of shock metamorphism. Reasonably, it is argued that there are no endogenetic processes known to produce, e.g., diaplectic glass or planar deformation features (PDFs) in quartz. Likewise, we argue that there are no endogenetic geologic processes known to have catastrophically destroyed the Jurassic limestones near Belchite. Therefore, geologists should be aware of their competence to establish in some cases an impact structure from pure field evidence. The time has come to give up the very limited point of view of some impact researchers that TEM analyses of PDFs or geochemical signature of the projectile are the ultimate requirement for establishing an impact structure. |

|

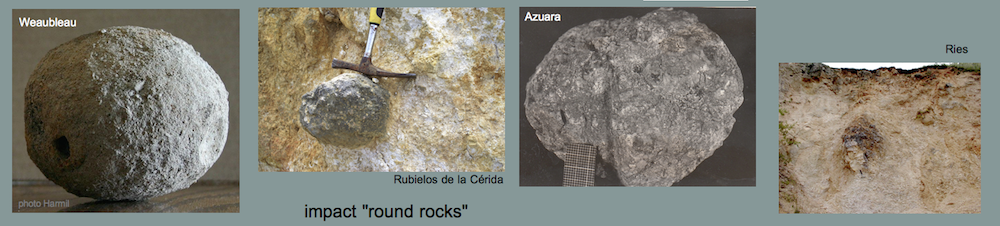

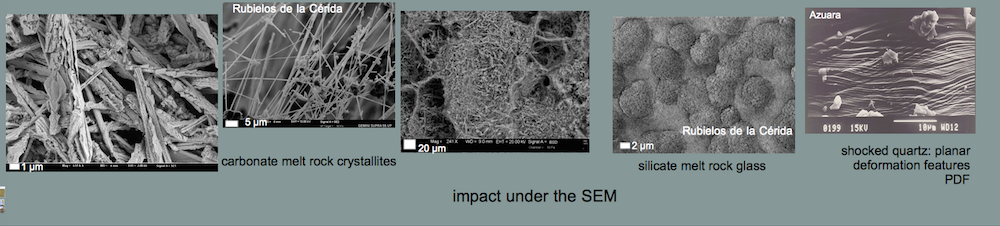

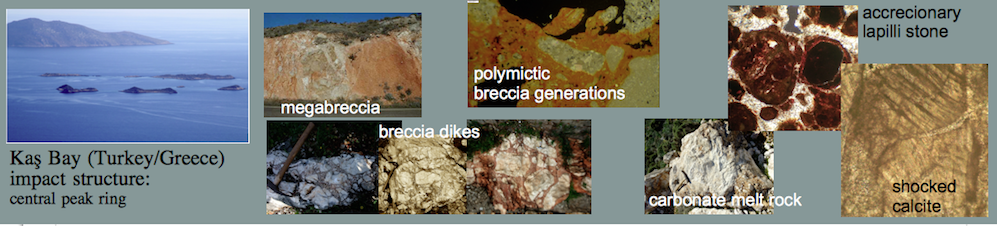

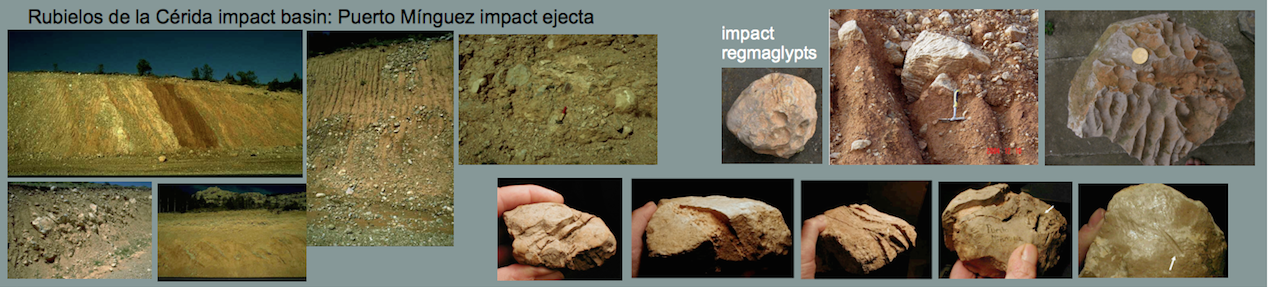

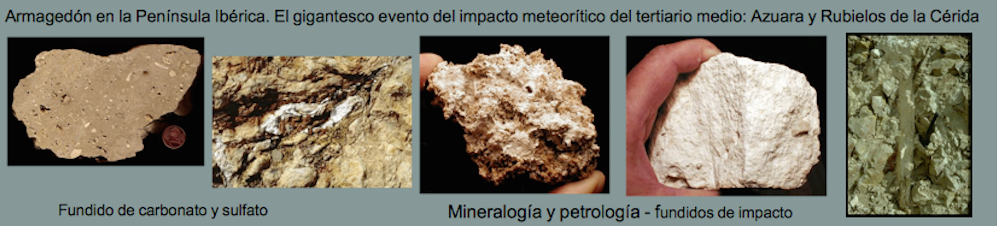

Rubielos de la Cérida impact structure (Spain): impact melt glass from the central uplift

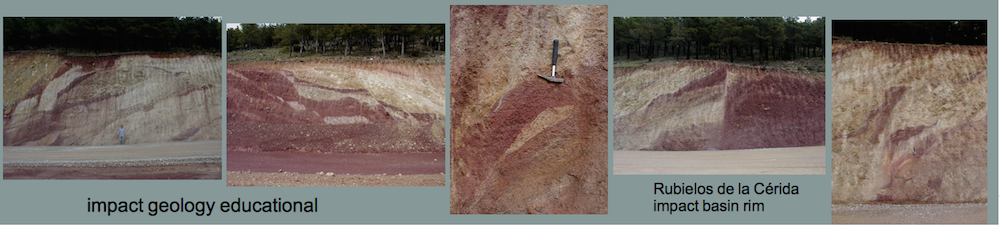

Rubielos de la Cérida impact structure, Spain: at the crater floor

This peculiar fold is exposed in a region of an extended megabreccia near the village of Barrachina in the Rubielos de la Cérida impact structure. The fold is portrayed by a competent, however heavily brecciated Lower Tertiary limestone layer. The core of the fold is a pulp of nearly pulverized carbonate rock without any regular internal structure. Only a few limestone fragments are preserved.

Interpretation: The exposure is assumed to be located at or near the crater floor of the Rubielos de la Cérida impact structure (for more details see:

where giant rock masses moved in the excavation and modification stage of impact cratering to form the now exposed megabreccia. The fold is interpreted to be the result of a high-pressure injection of extremely brecciated material from below. A tectonic origin of this peculiar structure is hardly to understand. Local geologists (from the Zaragoza university and the Center of Astrobiology, Madrid) suggest collapse by dissolution of gypsum to have produced the megabrecciation – need we comment?

Azuara impact structure (Spain) – Ries impact structure (Germany)

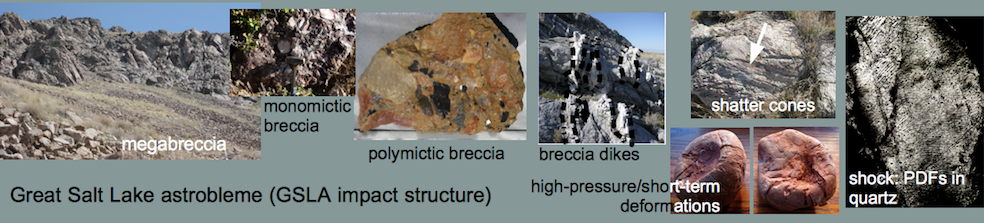

Ries impact structure (Germany); Azuara and Rubielos de la Cérida impact structures (Spain)

|

|||

|

|||

C CAguilón; Jurassic limestones (Azuara structure). Note the bedding in the base speaking against a tectonic fault.

|

D Dnear Santa Eulalia; Muschelkalk limestones (Rubielos de la Cérida structure). Note the block of bedded limestone floating in the highly brecciated material. |

||

| In all three cases, a tectonic interpretation of the layering offers considerable difficulties. | |||

Rubielos de la Cérida impact structure (Spain)

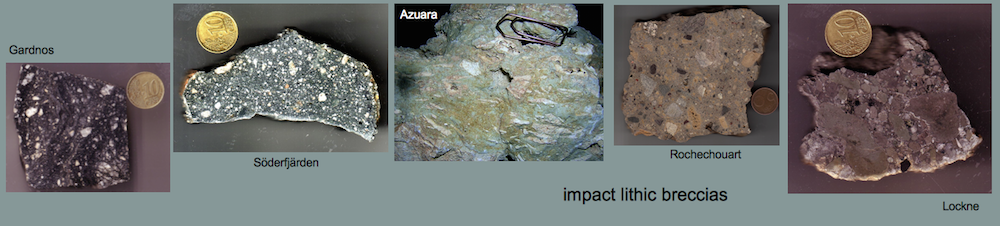

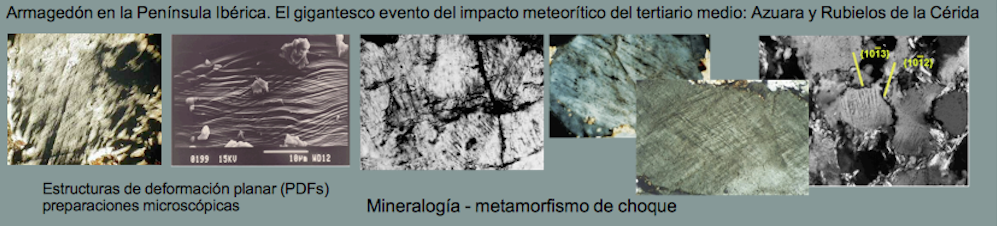

Azuara impact structure, Spain: shock metamorphism

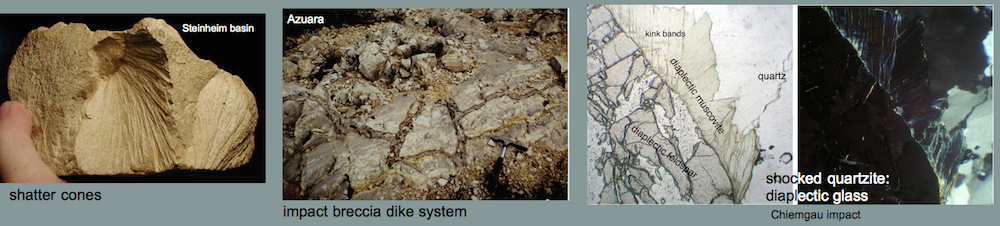

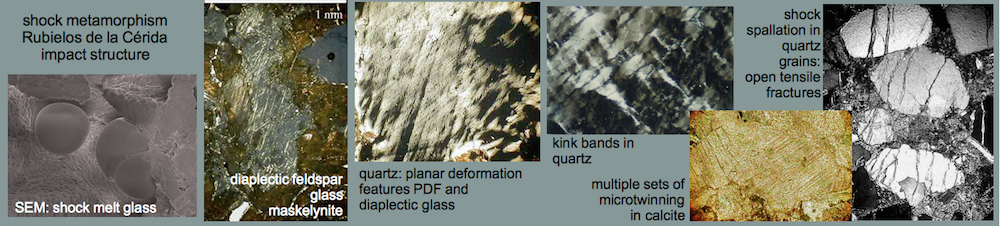

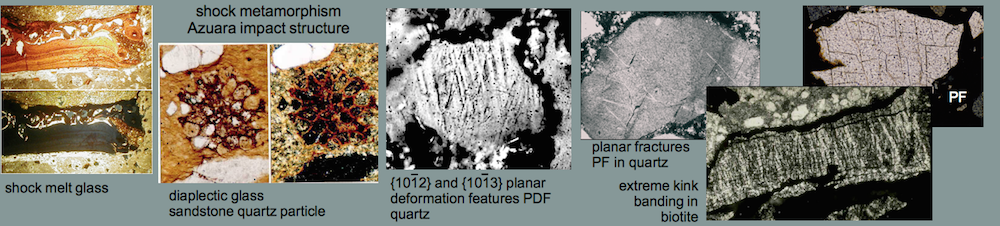

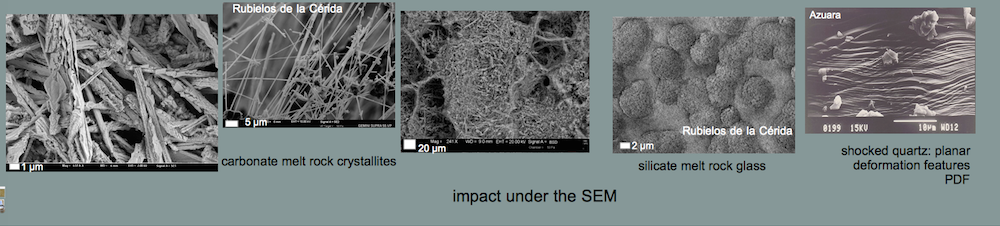

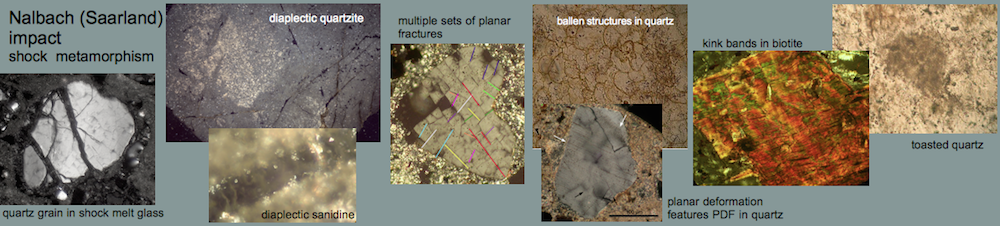

Highly shocked polymictic dike breccia (near Santa Cruz de Nogueras, 30660971E, 4553223N). Typical shock effects in the breccia are |

||||

A A

|

||||

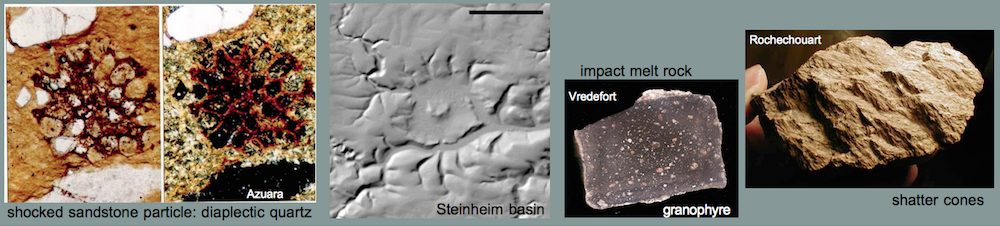

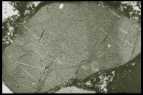

BB: Diaplectic glass; photomicrograph of a sandstone fragment completely transformed to diaplectic quartz; plane polarized light and xx nicols. Note that there are a few holes in the thin section not to be confused with diaplectic quartz grains. The field is 600 µm wide. BB: Diaplectic glass; photomicrograph of a sandstone fragment completely transformed to diaplectic quartz; plane polarized light and xx nicols. Note that there are a few holes in the thin section not to be confused with diaplectic quartz grains. The field is 600 µm wide.

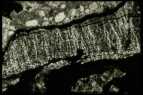

C: Planar deformation features (PDFs) in quartz grains; sandstone fragment from the shocked breccia. Photomicrograph, plane polarized light; the field is 800 µm wide. Note the large number of grains showing PDFs, their high density, the small spacing and the multiple sets. Up to five sets of different PDF orientation per grain have been observed in the dike breccia.

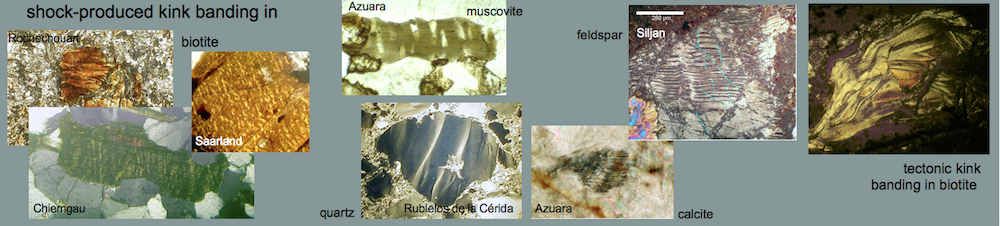

D: Planar fractures (PFs; cleavage) in quartz. Photomicrograph, xx nicols; the field is 450 µm wide. Note that at least six sets of different orientation can be observed. Cleavage in quartz is very uncommon in tectonically deformed quartz. In rare cases, rhombohedral fracturing is observed to occur in rocks which underwent strong regional metamorphism. In rocks from impact structures, PFs in quartz belong to the regular shock inventory. E: Kink bands in biotite from the shocked polymictic breccia. Photomicrograph, crossed nicols; the field is 840 µm wide. – Although kink bands can form under static conditions of strong regional metamorphism, the high frequency of the kink bands shown here, their narrow width, and their high kink-angle asymmetry point to shock deformation. The shock-metamorphic effects shown here correspond to a broad range of shock pressures. The melt glass, however, shows that parts of the breccia must have experienced shock peak pressures exceeding 500 kbars (50 GPa).

|

|

|||

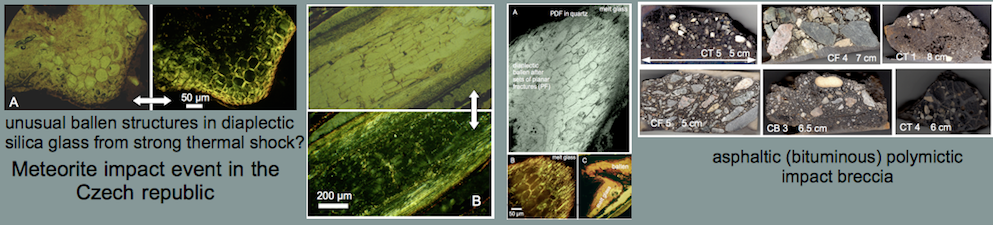

Rubielos de la Cérida impact structure, Spain:

Rubielos de la Cérida impact structure, Spain:

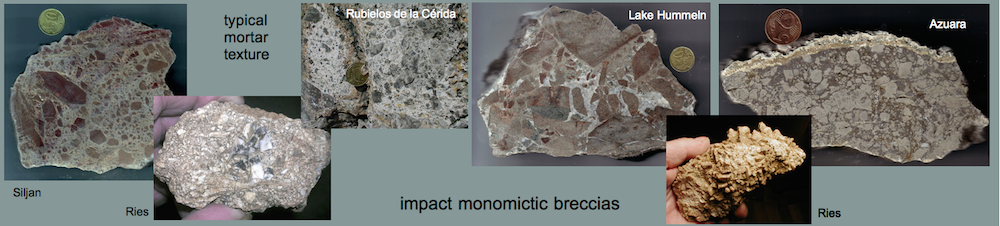

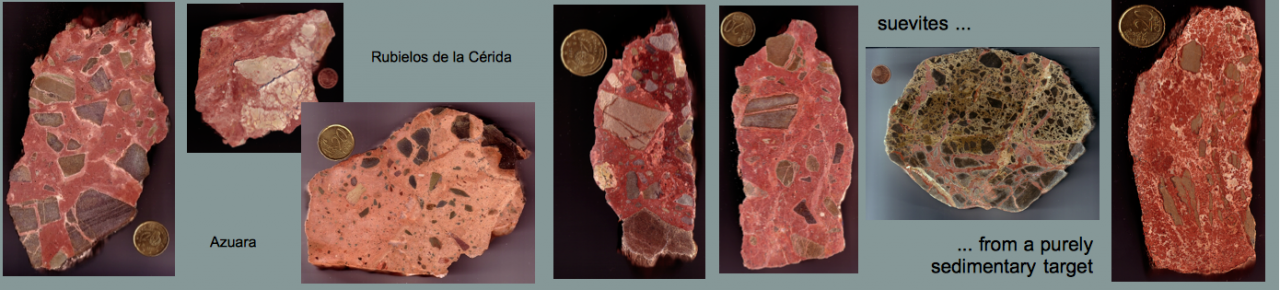

Part of a large (some 300 m size) quarry exposing limestones (Muschelkalk Fm.) drastically destroyed through and through (A).

Within the completely brecciated rocks (displaying gries brecciation and mortar texture), white blocks (up to cubic-meter size) of carbonate material (B) are intercalated.

The low-density, highly porous material shows a distinct vesicular texture (C – the field is 7 mm wide).

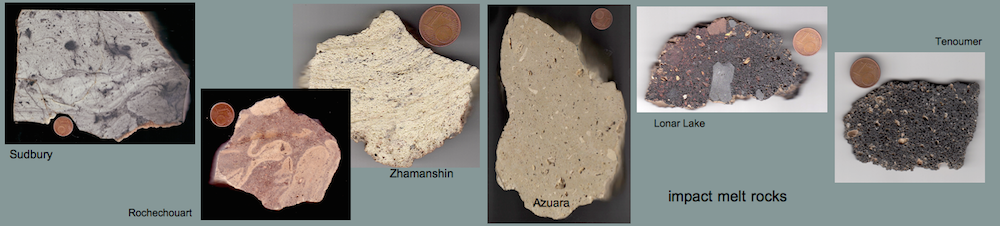

Interpretation: A compressive strength of perhaps 150 – 200 MPa (= 1.5 – 2 kbar) for these massive and dense Muschelkalk limestones assumed, they must have experienced pressures clearly exceeding these values not only locally but throughout the huge volume. Whereas a tectonic origin can be excluded without any doubt, deformations like that are expected to occur in the cratering process (excavation and/or modification stage) of large impact structures. The intercalated white vesicular material is considered to be the relics from decarbonization and/or carbonate melt produced by shock or strong frictional heating.

k.jpg)

k.jpg)

D

D E

E